PUBLICATIONS

Prologue

I wasn’t scared the night I was thrown in jail.

I was an archaeology student on a break. The night was moonless, and I was drunk. Singing at the top of my lungs, I staggered between my two Guatemalan friends, Pedro and Mateo. We were walking home from the little dusty town of San Benito where we had danced the Merengue all night.

“Amor, amor, amor,” I crooned into the night while six police officers crept behind us, then surrounded us. Two of them shouted orders as they grabbed my friends and shoved them to the dark roadside.

A cop, the one with two badges sewn on his shirt, stepped forward. He was about three inches shorter than me but something about the way he stood, and the way his left eyelid drooped, told me he could hurt me. He looked me straight in the face, nodding his head slightly. “You can go free if you give me a blow job.”

I laughed.

His scowl changed into a taunting smile revealing sharp, tight teeth. And he added, “Not just me!” He cocked his head toward the other cops who were standing like a pack of half-starved dogs.

“Fuck you,” I yelled and turned to leave.

He grabbed my arm and shoved me back toward the town center. The police pushed Pedro and Mateo as they marched ahead of me, silent. I was certain they wouldn’t hurt us. No, for me, Guatemala, the Land of Eternal Spring where I had been working on an archaeological site, was magical, with its Mayan Indians and ancient ruins set in emerald jungles. This police encounter was just another dream that would soon fade.

Inside the building’s crumbling walls, the police shoved Mateo and Pedro into a large cell among stocky Indian men who stared at us. They were silent, leaning against the bars, their eyes as steady and unfeeling as dead fish.

The cop marched me by them and through empty, dimly lit lime-green rooms with corners darkened by mold. His hand slipped across my back and my waist, up my hip then into my bag.

“Para! Stop it, don’t rob me!” I slurred. I could feel his hand digging into my purse. He looked away and led me to a room where a gaunt man sat waiting for me. He declared himself to be el juez, the judge. His dark-colored clothes hung on him like rags when he leaned forward over a pine table that sagged in the middle. A folding screen behind him barely concealed an unmade bed.

“Empty your bag on my table,” the judge ordered. Among my pens, comb, and wallet was a little red bag I’d never seen.

“Bueno,” he said jabbing at my bag and scooping out some marijuana with a gnarled finger. “Que es esto?”

I stared, incredulous. Was I being framed?

He leaned forward, stinking of booze, his mouth twitching as he offered me an alternative to jail. Pointing to the screen, the judge now spoke in English: “Fucky fucky and you go free.” He restated his offer, and I gave the same answer repeatedly until a cop hauled me off to the women’s jail.

_

The cell was so dark I could barely make out the cluster of bodies sleeping on the floor. I smelled something tangy and moist, but I couldn’t name it. I was sure I’d get out, but grim scenarios kept playing in my mind. When the morning sun finally slid across the floor, I could see Indian women huddling together on the floor. Squinting, I could nearly decipher words scrawled on the dull walls and a cross that someone had tried to carve over the cell door.

When the door finally opened, I could see barbed wire and broken glass on top of high walls that formed a courtyard. A tiny shed with a rusty barrel in one corner served as a fireplace where we could warm up food. Beside the courtyard was the female warden’s apartment.

A young Mayan man brought in three buckets: one was filled with sweet, watery coffee; another with thin porridge; and the third with stale tamale. Our food for the day. That first morning, when I was allowed one phone call to my family, the young man was silent and serious as he led me to the local phone center.

After that he was always friendly to me. “Good morning, Señorita,” he would say in that quiet Spanish that Indians use, stumbling, like me, over a second language. He wouldn’t look at my face, only at the ground, a trait I had noticed with other Indians. But because he was a guard, it made me feel uneasy. I couldn’t help but be suspicious. Everyone I had seen in jail was an Indian. So why was he, an Indian, working as a guard, while my cellmates, who seemed harmless, were locked up?

During the day I sat with the women along the edges of the courtyard, hiding from the hot white sun. They all dressed identically, their long black hair braided with bright ribbons. Their feet, calloused yellow like old plastic, peeked out from under colorful skirts, vivid splashes across the concrete. Kneeling on petates, thin straw mats, they’d speak softly as they embroidered or wove their traditional garments. One carried an infant on her back. She’d nestle in a shaded corner, tenderly clicking her tongue and murmuring to the baby.

Every evening we’d watch through an apartment window as the warden danced drunkenly with the cops. Then, sometimes still humming the dance melody, the warden would round us up and lock us in the jail room. We threw petates on the cement floor. The Indians would curl up like snails, wrapped in their rebozos, shawls, inching together for warmth, while I, lying there on my own, listened as their soft lilting sounds drifted toward me and soothed me to sleep.

In the early morning the women sat in the courtyard, busy with their weaving. It passed the eternal hours and deflected the question of what might happen next. It was their escape and their way of telling the story of their lives. Each design, every thread, told the tale of the language they spoke, the village and family they cared for, and the faith they nurtured. The weaving techniques and designs had been handed to them from woman to woman, grandmother to granddaughter for hundreds of years. It was their story and their escape.

Mine was writing. The Mayan guard bought a notebook, a pen, and cigarettes for me. Through writing I traveled away from the impenetrable walls, the Mayan women and the baby who grew sicker each day. I would daydream or write about the past when my family traveled and lived in many countries. Our father took us on trips to teach us about the world and to bring us together as a family. We stayed in fine hotels, but as we drove around or sat on trains, I always looked out the window at the shanties or the Bedouins riding camels and fantasized about going off into the desert with them or sitting in the shanties listening to stories. Something about these scenes spoke to my soul.

But it was the Egyptian temples that first gave me permission to harbor fantasies about being an archaeologist. The hieroglyphics told a story, a story thousands of years old. I was only twelve and I wondered: was it like my story? Did some words resound between us? I had a sense that there was a common thread between the stories that made us; that our stories mirrored each other in different languages. As did our gods: Ra, Allah, Jesus.

These experiences eventually brought me to this Mayan culture. Not to the ancient past when Mayan kings and queens built sprawling cities deep in the jungle but today, here, sitting between the jail walls. I wondered exactly what these particular Mayan women’s designs meant and perhaps the women wondered where my scrawling took me. Was there any connection between us outside of these walls? Their stories. My story.

My other escape was getting to know the women a little. They only spoke Kaqchiquel with each other, reserving their little bit of Spanish for the warden and me. An older Mayan woman made friends with me first. She dressed identically to the others but wore gaudy red plastic dangling earrings. She may have been somewhat wealthy because her two front teeth were outlined in gold.

“Adios,” she said, her hand grazing my arm. Neither one of us was going anywhere but I had learned Indians sometimes use that, adios, to say hello.

“Adios,” I answered.

“What do you call yourself?” she asked in Spanish.

“Clémence,” I told her.

“Eh?”

“Clemencia.”

“Ah, Clemencia,” she responded, then shook her head. “No, Mincha,”

she renamed me and quickly added, “La Mincha,” my name in Kaqchiquel.

She started to caress my arm, murmuring, “Pobrecita, pobrecita, poor thing,” her eyebrows locked together, her mouth turned down like she was overwhelmed by deep pity for me. I felt a flush of shame. I was the one who should feel sorry for her; I was the one with power and money to get out of this godforsaken place.

After she spoke with me, others did too. At first when I asked why they were locked up, they answered in wretched voices: “Aye Dios, I couldn’t feed my family. There was no corn to make tortillas. No salt. So, I made kusha, moonshine, to sell. That’s why I am here.”

Even the woman with the baby chanted the same refrain: “Yes, I couldn’t feed my family, so I made kusha.” She had bags under her eyes and was the only one whose voice sounded husky, as if she smoked.

“Do you smoke?” I asked, offering her one of my cigarettes.

“No,” she answered timidly, tilting her head to kiss her wheezing baby. But it was when I finally had a laugh with the old lady that I started to feel close to her. We started talking about our brothers and sisters. For some reason I told her about the time I played a trick on my sister and put toothpaste in her shoes. She laughed but I was sure she was like the rest of them and probably had never even worn shoes or been able to buy toothpaste. Then she told me how when she was little, she had long eyelashes, very long eyelashes. Her sister had said, “Here, I will help so you can see better.” And she cut off her eyelashes. Then her mother came home and said, “Oh, no, what happened to your eyelashes?”

I loved that story because I pictured it happening in a home, a regular home like the one I came from, even though I knew that wasn’t true. Her life was in a hut. My life was in what she would see as a mansion: running water, electricity, separate bedrooms. But for a moment our stories replaced our loneliness with a laugh.

_

We had our laugh but over the next two weeks I heard bits and pieces of stories revealing a pain that had been buried. In school, I had learned about settlers conquering the New World and wars with Indians, but I had never thought much about it. Until now. The old lady explained to me how five of the Mayan women were from a village that soldiers entered. They burned it to the ground and shot all the men. The women were brought here.

The story sounded unbelievable, like an old tale from the Wild West, but this was today. Instead of cowboys killing Indians, it was Ladinos. When I asked why this was happening, the old lady whispered her responses as if it were some secret code, “It happens because we are Indiginas, Naturales, the Natural Ones.” “What happened that night?” the man started to grill me. I looked

And with those words she planted a seed in me. I wondered how these gentle women really got here. Who were they? What did they think about? What did they care about? Most of all, I sat there feeling a connection with these women—but what kind of connection? Was it just our immediate circumstances? These questions would haunt and finally drive me to investigate. But at that moment, I wanted to say something, to explain something about myself, yet I was confused about what to tell her.

She’d look at me, poised, her gaudy earrings bobbing beside her crusty brown skin. Her conviction overshadowed rancor, yet she was powerless. The matron stomped around us every day and proved the Mayan’s powerlessness when she refused the mother’s pleas to bring her baby to the hospital. Finally, I was able to bribe her, and the baby saw a doctor, but it was too late.

It was even almost too late for these growing friendships. I was getting restless. I had heard about people forgotten in jails. But I was innocent. My government would help me. I had contacts and some money. When, I wondered, would they get me out of this place? I planned. I surveyed the courtyard wall. I could stand on the trashcan by the little tin shed, shimmy up the wall, leap somehow over the barbed wire and broken glass at the top, and then, I guessed, jump. It was a good ten feet, but I could make it. I never made plans beyond those. What I would do on the other side. Run? Keep running?

Each day I waited for lunch. Not for the food, since almost every day we had tamales wrapped in soggy cornhusks, but for the way we stood together around the barrel warming the tamales, me towering over the women as they prayed. They would whisper to God, then click their tongues making what sounded to me like bird trills. Then they’d turn to me to say, “Gracias, Nan. Thank you, Mother,” as if I had husked the corn and made the tamales. And it was the gentle way they always spoke to me in that tiny tin shed that finally made me break down and cry.

As if my weeping was a divine request, on that same day two men dressed in black followed the warden into our courtyard. They were somehow related to the US Embassy. Outreach workers. Volunteers. I didn’t know. One was a Ladino, the other, a man with a square body, short-cropped hair, wire-rimmed glasses and a demeanor that announced official business. It had been a month.

“What happened that night?” the man started to grill me. I looked at his well-shaven face, his kind, intelligent eyes and soft skin, and wondered what he was thinking. It was hot, noontime hot. The women were standing by the kitchen, very still, watching us. So still, eyes unmoving, as if they weren’t breathing.

I told him every detail of that night and when I finished my story, he paused, crouched beside me. I knew he didn’t believe me, so I told him, “Go visit the judge and you’ll see.”

I sat alone, uneasy under the women’s gaze, uneasy with my relief. Such relief! I knew I would walk out of that place. Here was my government. My protectors. Yet I felt cowardly. I leaned against the wall until the old lady came over, sat next to me, took my hand.

“God will protect you,” she assured me as if, once again, I was the one who needed comforting. “We are all praying for you.” She stroked my head and sat holding my hand as if in a vigil. The sun burned down on us. I felt dizzy.

The men returned two hours later, laden with Cokes and cakes. When they had walked into the drunken judge’s office, he had shouted, “You smoke marijuana!” They saw the screen and bed and smelled the guaro on his breath. He was the best evidence that my story was true. But the truth didn’t matter.

The embassy men demanded, “Give us five hundred dollars so we can bribe the pharmacy to say it wasn’t marijuana.”

“No,” I said. I looked around, somehow imagining I still had leverage even in jail. “I won’t do it!” I added, “I am innocent.”

Like hens clutched together in a corner, the women watched. A tightness in my throat grew so intense, I wasn’t sure I could speak. It was still hot. Squatting in the courtyard beside me, the consul leaned over and touched my shoulder, “You don’t understand. Someone has to be guilty. If you don’t do this, you won’t get out.”

When I packed my few belongings, the women clicked their tongues and took turns praying over me and patting my head. I cried. For them there would be no lawyers, no money. They couldn’t even fuck their way out of that hole because they were Indians, Naturales. After all that time locked up, it was when I was leaving that I finally got scared—of what I had learned about life and where that might take me.

_

Months later, back in my family home outside of Washington DC, even though they knew I had been in jail, no one spoke with me about jail, and I didn’t mention it either. Yet it hovered in the recesses of my mind, emerging to sabotage my dreams. I got some work but even the life I imagined for myself in archaeology no longer had luster. I felt something pulling me in another direction, but I couldn’t make sense of it.

After the Guatemalan jail, my eye was critical of everything around me. Every time I opened the refrigerator, the wealth and opulence of American people repelled me. Yet I couldn’t drown out or condemn anything or anyone totally. This was my world. And the reason I was free, out of jail, was because I belonged to this world.

But just because you belong, doesn’t mean you feel you belong.

After my time in jail, I was filled with a rage about the condition of the incarcerated women. I wanted to understand more about their lives. I stalked bookstores and libraries for information, any kind of information. I read ethnic studies, archaeological reports and international surveys. Soon I fell under the spell of the great Guatemalan writer, Miguel Angel Asturias, who began to unravel the mystery of their culture and the brutal forces surrounding it. He brought me into huts and then into the high courtrooms where decisions that were made by the few affected many. He led me to other Latin writers who also fleshed out worlds often hidden from our eyes yet struggling to survive. I went to the Library of Congress, in and out of the Smithsonian. There, I was in the center of world knowledge, and I was discovering facts about women, about Guatemala. Yet it wasn’t tangible. It didn’t bring me to the meaning or allow me to really understand the people. The image of the women in jail followed me everywhere. The prayers they whispered at my departure urged me along. I could almost feel the way each one touched my head, then my shoulders, whispering a prayer that was pushing me toward something I couldn’t quite discern. Then I got a sign.

I walked into my favorite café clutching Miguel Angel Asturias’s Hombres de Maiz and sat down next to a table of three young men in an animated conversation. Normally, even in the midst of chaos, I can concentrate on a good book, but as I sat down, I heard the words “secret police,” so the urge to eavesdrop was irresistible and soon I was sitting at the table with them. The words “Haiti,” “Duvalier,” and “vodou” were DOWN TO THE BONE

tossed back and forth. I had heard of Baby Doc, Duvalier, but I hardly knew where Haiti was and it seemed to be an enigma to these men too, who I, now, knew were journalists. “The boat people” seemed to be arousing their interest. The Haitians, half-starved, they all agreed, arriving on US shores on rickety boats, seeking amnesty. The men were discussing who were these people really were. What were they really fleeing? Or was it just money they wanted? Part of the American Pie, one inserted as he sucked with relish on his cigarette so ashes floated between his words. Part of the American Pie. Heads nodded in agreement. The American Pie. The conversation went in circles, confusing, disruptive, contentious. It was filled with emotion.

I felt a bitterness rise up in me. After jail I was pretty sure it wasn’t just American Pie pulling people to these shores. The journalist sitting beside me had a similar view. In a month he would go to Haiti, to see for himself the truth behind the boat stories.

He befriended me, and listening to him as he planned for his journey and spoke about Haiti, something unexpected settled in me. I wanted to understand more about the Mayan women in jail, but it wasn’t just them. What about the other women of the Earth whom we never hear about in news or see on television except when there is a major calamity, an earthquake, or civil war? What about the Haitian women on those boats?

I decided that somehow I, too, would go to Haiti and learn the backstory, the life stories of women, the connections between our worlds. Then I would go to Guatemala. But I would start in Haiti. It was only seventy miles from the United States; it was cheap, mysterious and controversial. My family tried to talk me out of it. It’s dangerous, my father pleaded, go back to college.

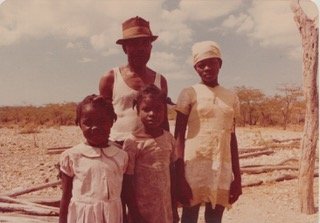

I didn’t listen, although there were moments I doubted myself. I was being pulled toward something. I didn’t have a background as a journalist like my friend, nor was I a sociologist, an activist, or even a feminist. But I did know how to speak French and, by then, Spanish. And I loved to read and hoped that would count for something. My only real preparation, as far as I could see, and later I was proven right, was my life experience. My father was a career man in the navy, and later I was to find out he was also a CIA agent. He worked like he lived, with a sharp and feverish intelligence, but also with enough humor to drag the seven of us around the world. Even this he did in his own original style.

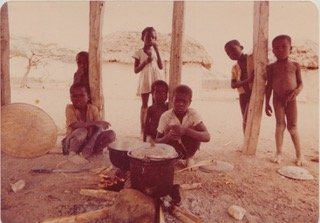

Unlike other fathers, despite the availability of international schools for diplomats or navy families, my father always chose for us to attend local Catholic schools. It didn’t matter what food they ate, what language they spoke, or if the playground was only a dirt courtyard. He wanted us to learn about the cultures where we lived in Africa, the Caribbean, and Europe.

I got a bit of grant money and made plans to immerse myself in a world unlike my own. I knew little about Haiti and it was a deviation from my course. But like many deviations, it forced me into a truth.

So, as unprepared as I was, the love of adventure and the women in jail finally gave me the gumption to board that plane to Haiti and land at the Port-au-Prince airport: Mayi Gaté Airport, Rotten Corn Airport. People said it was named after the area where it was located, but I doubted it. The name was my first taste of that Haitian wry humor—disdainful, ironic, and always brutally honest.